Get to know the Adélie penguin! // Darf ich vorstellen: der Adeliepinguin!

The first little guy I would like to introduce you to is the one I have chosen as the “header” of the website: The Adélie penguin Pygoscelis adeliae. Like all penguins, Adélies are flightless birds that are perfectly adapted to life at sea. Over millions of years their wings have become flipper-like and allow them to reach astounding speeds in water and dive to depths no other birds can reach. Contrary to popular belief, penguins are not restricted to cold regions. They only occur on the Southern hemisphere though; you won’t find them in the Arctic. The majority of the 18 penguin species actually inhabits sub-temperate and temperate regions.

So, what is special about the Adélie penguin, you wonder? Well, besides the better known emperor penguin, the Adélie penguin is the only true Antarctic penguin species (remark: there are two other species that inhabit parts of the Antarctic Peninsula but occur further north otherwise – we’ll get to know them in separate posts). It occurs all around the Antarctic continent and breeding colonies can be found as far south as 77°. Due to their hostile environment, they have a short breeding season: The Antarctic summer. That’s when they return to their colonies to look for their partner from previous years. Or a new partner. Penguins have the reputation of being very faithful. However, it’s not that simple. Some species are, but many will choose a different partner after a few seasons. When you see a group of penguins, you will hardly be able to tell the difference between males and females. Their plumage looks the same. Males are typically a bit bigger and heavier. The safest way to tell the difference: Catch them “in flagrante” 🙂 .

Male and female penguins do not only look the same. They also share their parental duties equally and take turns incubating the eggs and later guarding the chicks – when it comes to gender equality penguins are way ahead of us 😉 . By the end of the summer, when the chicks are old enough to fend for themselves, the parents will molt. Penguins renew their plumage once a year after the breeding season, before leaving their colonies for the next eight months.

The Adélie is a very peculiar looking penguin. With their completely black head and the flashy white ring around the eyes, they are easy to distinguish from other penguin species. Especially the eye ring makes them often appear startled. These penguins were named for “Adélie Land” in East Antarctica. This part was discovered by the French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville in 1840 who named it after his wife Adéle.

Discovery of “mega colony” – thanks to penguin poo!

Even today new penguin colonies are still being discovered – one of them recently on the ominous Danger Islands. This archipelago of nine islands is located at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula – the tourism “hot spot” of Antarctica. However, the Danger Islands are rarely visited. Ocean currents drive sea ice towards them and preclude access in most years. It had been known that Adélie penguins occurred in that area. However, there was an inventory of only one of the nine danger islands from the 1990s.

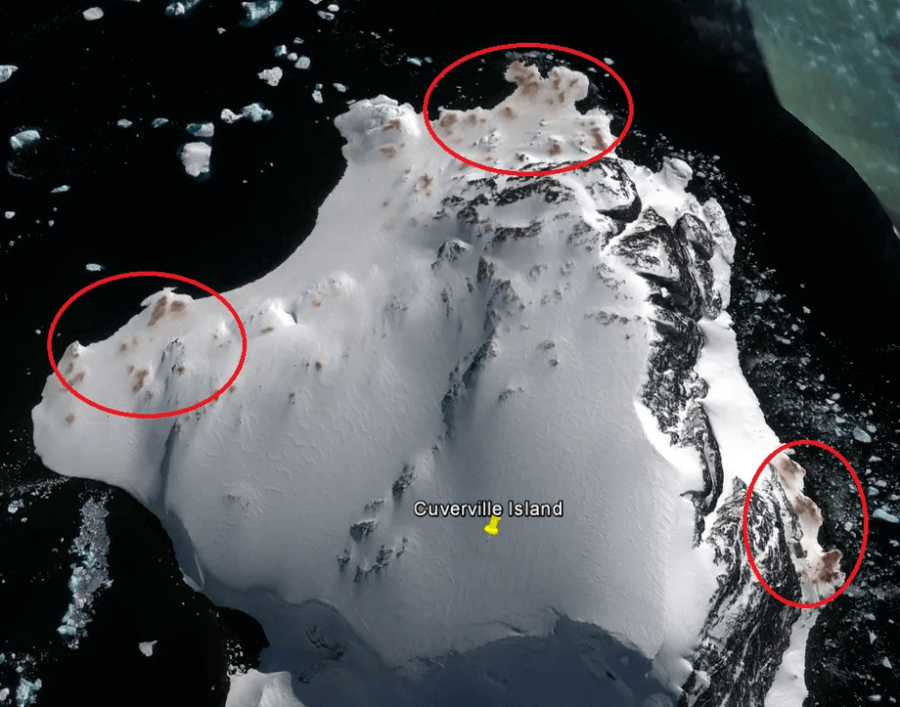

New technologies like drones have made counting nests in colonies much easier for researchers. However, on the Danger Islands even new colonies with hundreds of thousands of penguins were discovered very recently! The penguins themselves helped out and this is how: During the breeding season, when the penguins raise their chicks, the snow in and around the colony slowly turns reddish-brown due to the poo, also known as guano. The Antarctic Krill, the staple food for Adélie penguins, is responsible for this color. A few years ago, researchers developed an algorithm that detects this discoloration in the snow on satellite images. That’s how they discovered the “mega colony” on the Danger Islands and with the help of drones counted over 750,000 breeding pairs of Adèlie penguins (Borowicz et al. 2018).

What’s the outlook for Adélie penguins?

The total population is estimated at about 3.8 million breeding pairs (BirdLife International 2018). The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists the Adélies as “least concern”. In some colonies in East Antarctica the numbers have increased in recent years. At the Antarctic Peninsula, however, numbers are going down. The two major factors suspected to be responsible for the decline are climate change and fishing.

One of the main target species of commercial fisheries in Antarctic waters is Antarctic krill. About half if it is being used to feed farmed fish, the other half is turned into dietary supplements often sold as krill oil. Even though it should be a no brainer: Humans do not need Antarctic Krill for a healthy diet. For whales, seals and penguins, however, it’s crucial. Let’s leave the krill for those who actually depend on it.

Climate change is an obvious threat for species living in Antarctica. A temperature increase of our atmosphere of 1.3°C will lead to a population decline of about 70%. The main factor is the declining sea ice (Ainley et al. 2010). In contrast to some other penguin species occurring in the Southern Ocean, Adélie penguins depend on pack ice all year round. This makes them particularly vulnerable to climate change. But this also makes them one of the many species we might be able to preserve with determined action to cut global CO2 emissions.

Der erste kleine Kerl, den ich vorstellen möchte, ist der, den ich als „Kopfzeile“ der Website ausgewählt habe: Der Adeliepinguin Pygoscelis adeliae. Wie alle Pinguine sind Adelies flugunfähige Vögel, die perfekt an das Leben auf See angepasst sind. Über Millionen von Jahren sind ihre Flügel flossenartig geworden und ermöglichen es ihnen, im Wasser erstaunliche Geschwindigkeiten zu erreichen und in Tiefen zu tauchen, die kein anderer Vogel erreicht. Entgegen der landläufigen Meinung sind Pinguine nicht auf kalte Regionen beschränkt. Sie kommen jedoch nur auf der Südhalbkugel unseres Planeten vor, in der Arktis wirst du sie nicht finden. Die Mehrheit der 18 Pinguinarten lebt tatsächlich in gemäßigten Regionen.

Was ist das Besondere am Adélie-Pinguin? Nun, neben dem bekannteren Kaiserpinguin ist der Adélie-Pinguin die einzige echte antarktische Pinguinart (Bemerkung: Es gibt zwei weitere Arten, die Teile der antarktischen Halbinsel bewohnen, aber ansonsten weiter nördlich vorkommen – wir werden sie in separaten Beiträgen kennenlernen). Er kommt um den gesamten Antarktischen Kontinent herum vor und Brutkolonien gibt es bis zum 77 ° südlicher Breite. Aufgrund ihres unwirtlichen Lebensraumes haben sie eine kurze Brutzeit: Den Antarktischen Sommer. Zu dieser Zeit kehren sie in ihre Kolonien zurück, um nach ihrem Partner aus Vorjahren zu suchen. Oder nach einem neuer Partner. Pinguine haben den Ruf, sehr treu zu sein. So einfach ist das jedoch nicht. Einige Arten sind es, aber viele werden nach ein paar Jahren einen anderen Partner wählen. Wenn Du eine Gruppe von Pinguinen siehst, wirst du Männchen und Weibchen kaum unterscheiden können. Ihr Gefieder sieht gleich aus. Männer sind normalerweise etwas größer und schwerer. Der sicherste Weg, um den Unterschied zu erkennen: Ertappe sie auf frischer Tat :-).

Der Adelie ist auch ein sehr auffällig aussehender Pinguin. Mit dem komplett schwarzen Kopf und dem weißen Ring um die Augen sind sie leicht von anderen Pinguinarten zu unterscheiden. Besonders der Augenring lässt sie manchmal ein wenig erschrocken aussehen. Diese Pinguine wurden nach „Adélie Land“ in der östlichen Antarktis benannt. Dieser Teil wurde 1840 vom französischen Entdecker Jules Dumont d’Urville entdeckt, der ihn nach seiner Frau Adéle benannte.

Entdeckung einer „Megakolonie“ – dank Pinguinschei*e!

Noch heute werden neue Pinguinkolonien entdeckt – eine davon kürzlich auf den ominösen Danger-Inseln. Dieser Archipel aus neun Inseln befindet sich an der Spitze der Antarktischen Halbinsel – dem touristischen „Hot Spot“ der Antarktis. Die Danger-Inseln werden jedoch selten besucht. Meeresströmungen treiben Meereis auf sie zu und machen den Zugang in vielen Jahren unmöglich. Es war zwar bekannt, dass Adeliepinguine in diesem Gebiet vorkamen. Allerdings gab es eine Bestandsaufnahme nur von einer der neun Danger-Inseln aus den 90er Jahren.

Neue Technologien wie Drohnen erleichtern Forschern das Zählen von Nestern in Kolonien. Auf den Danger-Inseln wurden kürzlich jedoch sogar neue Kolonien mit Hunderttausenden von Pinguinen entdeckt! Die Pinguine selbst haben dabei geholfen und zwar so: Während der Brutzeit, wenn die Pinguine ihre Küken aufziehen, wird der Schnee in und um die Kolonie aufgrund der Hinterlassenschaften, auch Guano genannt, rotbraun. Der Antarktische Krill, das Grundnahrungsmittel für Adeliepinguine, ist für diese Farbe verantwortlich. Vor einigen Jahren entwickelten Forscher einen Algorithmus, der diese Verfärbung im Schnee auf Satellitenbildern erkennt. So entdeckten sie die „Megakolonie“ auf dem Danger Archipel und zählten mit Hilfe von Drohnen über 750.000 Brutpaare von Adeliepinguinen (Borowicz et al. 2018).

Wie sieht die Zukunft der Adeliepinguine aus?

Die Gesamtpopulation wird auf etwa 3,8 Millionen Brutpaare geschätzt (BirdLife International 2018). Die Naturschutzunion stuft Adelies zurzeit nicht als bedroht oder gefährdet ein. In einigen Kolonien in der Ostantarktis hat die Zahl in den letzten Jahren zugenommen. Auf der Antarktischen Halbinsel gehen die Zahlen jedoch zurück. Die beiden vermulich verantwortlichen Hauptfaktoren für den Rückgang sind der Klimawandel und die Fischerei.

Eine der Zielarten der kommerziellen Fischerei in antarktischen Gewässern ist der Antarktische Krill. Etwa die Hälfte davon wird zur Fütterung in Aquakulturen verwendet, die andere Hälfte wird zu Nahrungsergänzungsmitteln verarbeitet und als Krillöl verkauft. Auch wenn es offensichtlich sein sollte: Kein Mensch braucht Antarktischen Krill für eine gesunde Ernährung. Für Wale, Robben und Pinguine ist er jedoch überlebenswichtig. Überlassen wir den Krill denen, die tatsächlich davon abhängen.

Der Klimawandel ist eine offensichtliche Bedrohung für in der Antarktis lebende Arten. Ein Temperaturanstieg unserer Atmosphäre um 1,3 ° C führt zu einem prognostizierten Bestandsrückgang von ca. 70%. Der Hauptfaktor dafür ist das abnehmende Meereis (Ainley et al. 2010). Im Gegensatz zu einigen anderen im Südpolarmeer vorkommenden Pinguinarten sind Adeliepinguine das ganze Jahr über auf Packeis angewiesen. Dies macht sie besonders anfällig für den Klimawandel. Dies macht sie aber auch zu einer der vielen Arten, die wir mit entschlossenen Maßnahmen zur Reduzierung unserer globalen CO2-Emissionen erhalten können.

2 Antworten

Hi Hannah

Happy New Year for 2021.

Thankyou for making our Xmas/New Year 12 months ago so special.

Do you have any news of the Captain and/or the rest of the expedition staff.

Lovely to read your current articles

Hi Rhonda, hi Rod,

thank you so much for your message! =) I wish you a happy new year, too! I am happy you’re still thinking about your cruise and hope the memories will stay with you forever. Everyone is fine as far as I know, just dearly missing our penguin and seal friends from the South. Fingers crossed that we will all get back to exploring and traveling again sooner rather than later.

All the best!